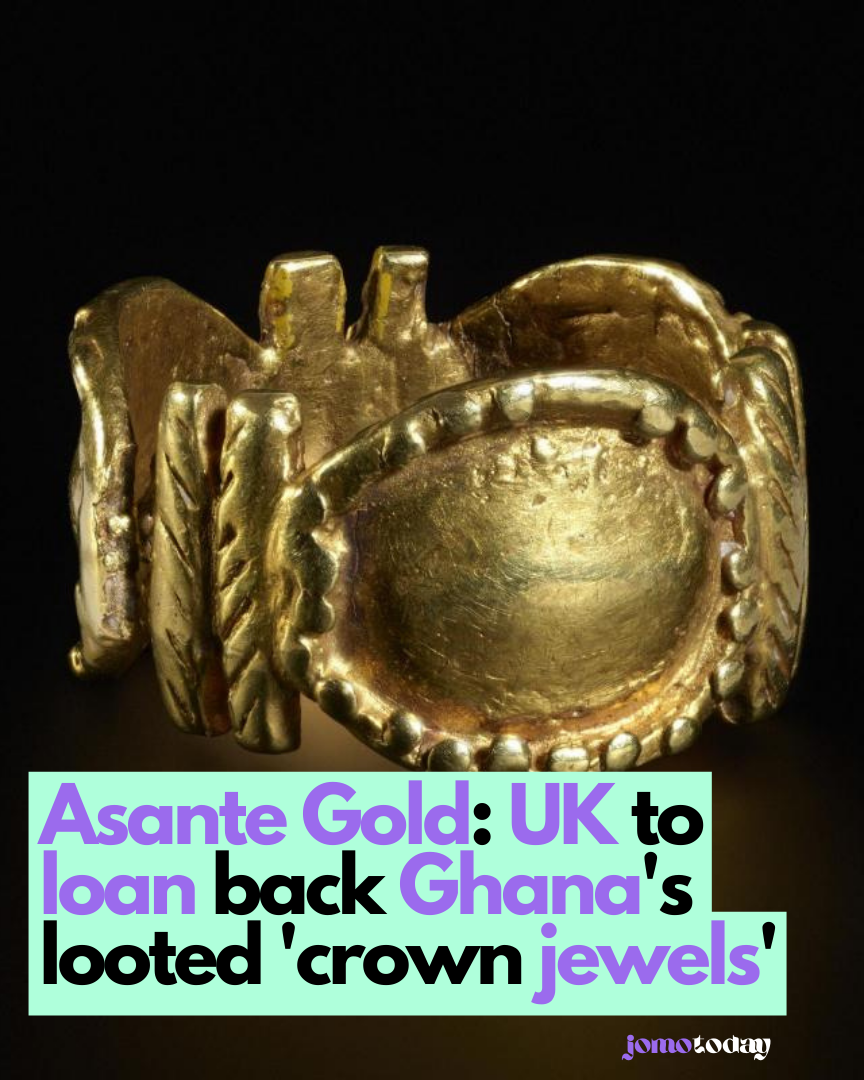

Asante Gold: UK to loan back Ghana’s looted treasures taken 150 years ago, in a potential model for similar disputes. The BBC uncovered this development, signifying a significant step in addressing historical looting.

Treasures, Gold taken 150 years ago will go back, the BBC can reveal, in a possible model for other disputes.

The BBC can disclose that a gold peace pipe is among 32 items set to return under long-term loan agreements.

Of these items, 17 are from the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A), while 15 originate from the British Museum.

Ghana’s lead negotiator expressed hope for “a renewed sense of cultural cooperation” following years of resentment.

Certain UK national museums, including the V&A and the British Museum, are legally prohibited from permanently repatriating disputed items in their collections. Consequently, loan arrangements like this facilitate the return of objects to their countries of origin.

However, some nations claiming ownership of contested artifacts are concerned that loans could be construed as acquiescence to UK ownership.

Tristram Hunt, the V&A’s director, likened the gold court regalia to “our Crown Jewels.”

The items slated for loan, many of which were acquired during 19th-century conflicts between the British and the Asante, encompass a sword of state and gold insignia worn by officials tasked with purifying the king’s spirit.

Mr. Hunt emphasized the importance of considering fair sharing arrangements for objects in museums that have origins in war and looting during military campaigns, expressing a responsibility towards the countries of origin. He suggested that establishing partnerships and exchanges could be beneficial without jeopardizing the integrity of museums.

However, Mr. Hunt clarified that the newly proposed cultural partnership does not imply restitution by indirect means, indicating that it does not aim to permanently return ownership to Ghana.

Under the three-year loan agreements, with the possibility of extension for another three years, the items will be loaned not to the Ghanaian government but to Otumfo Osei Tutu II, also known as the Asantehene, who attended King Charles’s coronation last year. Despite his influential ceremonial role, the Asantehene’s kingdom is now part of Ghana’s modern democracy.

The artifacts will be exhibited at the Manhyia Palace Museum in Kumasi, the capital of the Asante region, to commemorate the Asantehene’s silver jubilee. These Asante gold artifacts hold significant cultural value as symbols of the Asante royal government, believed to carry the spirits of past Asante kings.

The significance of these artifacts to Ghana mirrors that of the Benin Bronzes—thousands of sculptures and plaques looted by Britain from the palace of the Kingdom of Benin, now in southern Nigeria. Nigeria has persistently demanded their return for decades.

Nana Oforiatta Ayim, acting as a special adviser to Ghana’s culture minister, emphasized to the BBC: “These artifacts are not mere objects; they hold profound spiritual significance. They represent an integral part of the nation’s essence, embodying pieces of our collective identity. This loan marks a meaningful beginning, coinciding with the anniversary of the looting, and signifies a step towards healing and remembrance of the violence endured.”

The United Kingdom’s museums house numerous items taken from Ghana, including a renowned gold trophy head, among the most iconic pieces of Asante regalia.

The Asante civilization once commanded one of West Africa’s most potent and influential states, engaging in trade of commodities such as gold, textiles, and enslaved individuals.

Renowned for its military prowess and affluence, the kingdom attracted Europeans to what they later termed the Gold Coast. Britain engaged in multiple conflicts with the Asante during the 19th Century.

Following an Asante assault in 1874, British forces conducted a “punitive expedition,” in colonial parlance, resulting in the pillaging of Kumasi and the confiscation of many treasures from the palace.

held on April 18, 1874, at Garrards, the esteemed London jewellers responsible for maintaining the UK’s Crown Jewels.

Among these items are three substantial cast-gold pieces referred to as “soul washers’ badges” (Akrafokonmu), which were worn around the necks of high-ranking officials at court tasked with purifying the soul of the king.

According to Angus Patterson, a senior curator at the V&A, the acquisition of these items in the 19th century served purposes beyond mere accumulation of wealth; it also involved the removal of symbols of government or authority, constituting a profoundly political act.

The British Museum, in a parallel move, is lending a total of 15 items, some of which were looted during a subsequent conflict in 1895-1896. These include the Mpomponsuo, a ceremonial sword of state.

A ceremonial cap, known as a Denkyemke and adorned with intricate gold ornaments, was traditionally worn by senior courtiers during coronations and important festivals.

Additionally, the British Museum will be showcasing a cast-gold model lute-harp called the Sankuo, which was not part of the looted artifacts. This item serves to emphasize its nearly two-century-old association with the Asantehenes.

The Sankuo was bestowed upon the British writer and diplomat Thomas Bowdich in 1817. He noted that it was intended as a gesture of goodwill from the Asantehene to the museum, symbolizing the wealth and prestige of the Asante nation.

Can objects be lent back to a country that accuses you of stealing them?

It presents a potential solution to legal constraints in the UK that might not satisfy nations seeking to rectify historical grievances.

The Parthenon Sculptures, also known as the Elgin Marbles in the UK, exemplify this dilemma. Greece has persistently requested the return of these ancient sculptures currently housed in the British Museum. George Osborne, chair of the museum’s trustees, recently expressed interest in finding a “practical, pragmatic, and rational” approach, exploring partnerships that, in essence, sidestep questions of ownership.

The agreement with the Asantehene reflects a similar compromise, accommodating the Asante king within British legal confines.

While such arrangements may resolve issues for specific stakeholders, they may not be viable for other countries. Nigeria, for instance, would likely decline a loan of the Benin Bronzes, as would Ghana’s government in a similar situation.

However, according to Mr. Hunt, agreements between institutions like the V&A, the British Museum, and the Manhyia Palace Museum, while not solving the underlying issue, can serve as a starting point for dialogue and potential resolution.

Ms. Oforiatta Ayim, advisor to the Minister of Culture in Ghana, affirmed that the notion of securing a loan would undoubtedly provoke anger, expressing hope for the eventual permanent return of the items to Ghana. She emphasized the historical circumstances of theft and the rightful ownership of the Asante people over the artifacts.

The British government maintains a “retain and explain” policy for state-owned institutions, wherein contested objects are retained with their contextual explanations provided. Both the Conservative and Labour parties have shown no inclination to amend existing legislation, citing the British Museum Act of 1963 and the National Heritage Act of 1983, which prevent the deaccessioning of items from certain prominent institutions’ collections.

Advocating for a legal change, Mr. Hunt proposes granting museums more autonomy while establishing a committee for appeals regarding restitution requests. Concerns have been raised about potential loss of prized items from British museums in the future, with some likening it to opening Pandora’s box, as former Culture Secretary Michelle Donelan remarked regarding the Parthenon Sculptures.

However, Mr. Hunt noted that very few of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s 2.8 million items have ownership disputes.

Another concern revolves around the potential for contested items lent out to never be returned.

Ghana’s chief negotiator Ivor Agyeman-Duah dismissed this fear, stating, “Adherence to existing agreements is paramount; one must not act against them.”

Among the captivating Asante gold artifacts housed in the UK is the trophy head, prominently featured in the Wallace Collection. This particular artifact, like many others, was seized by British forces and later acquired in the 1874 auction.

The Royal Collection also boasts similar objects, including another gold trophy head fashioned as a mask. Such artifacts symbolized vanquished adversaries and were affixed to ceremonial swords as part of the state regalia.

The question of whether these artifacts will ever grace displays in Ghana remains uncertain, with Mr. Agyeman-Duah opting for a cautious approach.

However, as Britain grapples increasingly with the cultural remnants of its colonial history, such agreements may serve as diplomatic and pragmatic methods for addressing the past and fostering improved relations in the future

It’s a fascinating tale of the UK promising to loan back Ghana’s looted ‘crown jewels.’ For decades, these treasures have been far from home, housed in foreign museums and private collections. Now, there’s a glimmer of hope for their homecoming. The decision to return the Asante Gold is not only a step towards righting historical wrongs, but also a symbol of cultural reconciliation. This move represents a significant milestone in the ongoing efforts to repatriate cultural heritage to their rightful places. It’s heartening to witness such positive strides being taken towards acknowledging and rectifying the injustices of the past. Let’s keep our eyes peeled for more developments on this heartening story of cultural restoration and justice.

Read More: Pants, moustaches and bird livers among missing museum artefacts

Leave a Comment