JS was an iconic magazine that revolutionized the concept of the Indian teenager. It was chatty, irreverent, and engaged, shaping Indian cosmopolitanism.

Chatty, irreverent and engaged, JS was more than a magazine – it shaped an Indian cosmopolitanism.

The nearly forgotten JS, a cult youth magazine of the 60s and 70s, played a unique role in shaping the Indian teenager. Soutik Biswas of the BBC delves into its nearly defunct archives, revealing a publication that vividly captured the hope and desperation of those decades in India with profound insight, cleverness, and energy.

During 1975, daring Indian journalist Khalid Mohammed managed to sneak into Mumbai’s international airport, then Bombay, armed with a tape recorder, aiming to meet Paul McCartney en route to Australia with his band, Wings.

The outcome was an interview filled with wit and banter as they discussed rumors of a Beatles reunion, the future of rock music, and life with Wings.

At one juncture, Mohammed queried McCartney about the increasing commercial nature of his music.

“Our next album won’t be commercial. It’ll be experimental. Twenty-minute songs and backwards – just for you,” quipped the former Beatle.

McCartney’s candid interview epitomized the spirit of JS, derived from Junior Statesman, a groundbreaking companion to a prominent and rebellious newspaper based in Kolkata, then known as Calcutta. Shashi Tharoor, MP and author, highlighted, “Anyone who was a teenager in India between 1967 and 1977 would readily attest to the extraordinary impact JS had on their generation.”

At the age of 11, Mr. Tharoor made his writing debut by crafting a six-part World War Two adventure for JS, earning a noteworthy 50 rupees. He recounts encounters with admirers, even middle-aged individuals, who vividly recall passages he himself had forgotten.

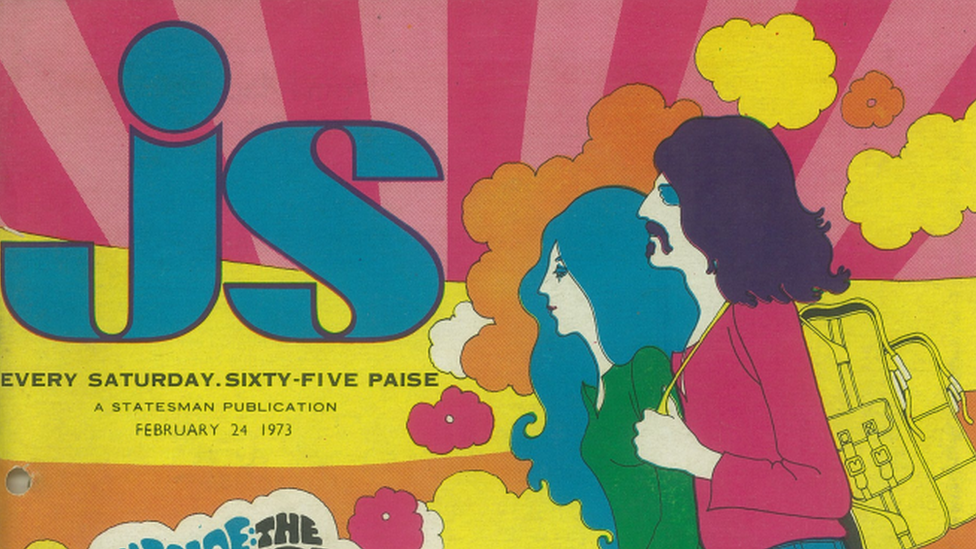

JS burst onto the scene in February 1967 with The Beatles gracing its inaugural cover, swiftly resonating with the urban youth amidst a time of scarcity, escalating prices, and unemployment in the nation. An era devoid of vibrant television, relying instead on books and music, as most publications were deemed dreary and conventional.

Under the guidance of Desmond Doig, an India-born Anglo-Irish figure previously affiliated with The Statesman as a roving reporter, JS was steered by a team of eager college graduates. It swiftly cultivated a reputation for its spirited, conversational tone, consistently connecting with its audience.

According to journalist and author Bachi Karkaria, who commenced her writing journey as a teenager within JS, the magazine acknowledged the transitional phase from childhood to adulthood, creating its own distinctive identity and narrative.

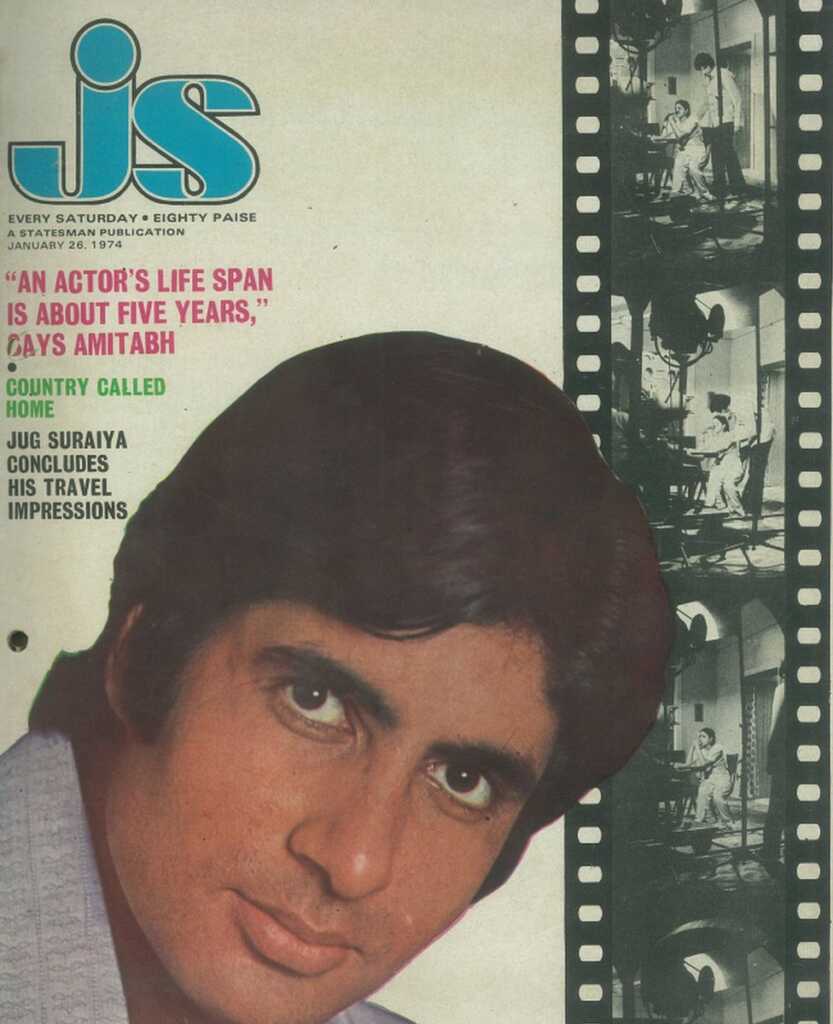

The magazine’s colorful covers harmonized global and local elements: vibrant pop-art illustrations, Bollywood luminaries like Amitabh Bachchan and Rishi Kapoor alongside figures like Led Zeppelin and the Beatles, and the lively hues of Bihar state’s folk arts. Notably, large fold-outs of teenage icons were an exclusive attraction. Jug Suraiya, a prolific writer for JS, encapsulated it as more than a mere publication, labeling it a cultural phenomenon in his memoirs.

Quirk was always just a few magazine covers away. One headline blared “The Day The Martians Landed,” depicting looming alien spaceships, while another pondered “ESP: Fact Or Fiction,” nestled among a series exploring eternal controversies. Mr. Tharoor remarked that the articles swung between the tone of Seventeen magazine and a relatively sober Hunter S. Thompson.

Predictably, there was hardly ever a dull moment.

In 1975, JS, relying on “unimpeachable sources,” covertly pursued George Harrison in Kolkata during the music icon’s brief 30-hour visit as part of an Indian pilgrimage.

According to CY Gopinath, the magazine’s meticulous reporter, the Beatles legend was observed engaging in meditation, practicing yogic postures, counting beads on a rosary, visiting temples, commissioning an image of the Hindu goddess Kali, and enjoying a lunch of Bengali cuisine at a friend’s residence.

He even managed to snatch a two-minute conversation during which Harrison answered half a dozen questions, had seven pictures taken, and gave an autograph. The magazine carried a picture of the long-haired musician with the caption: “George Harrison has gone Hindu pilgrim.”

There was no dearth of controversies. Fusion music pioneer Asha Puthli, crestfallen after a concert in Mumbai in the aid of the hungry, told the magazine that most of the audience “seemed more interested in eating ‘phoren’ (foreign) food”.

“To add to it, the sound system was bad. I actually cried, you know.”

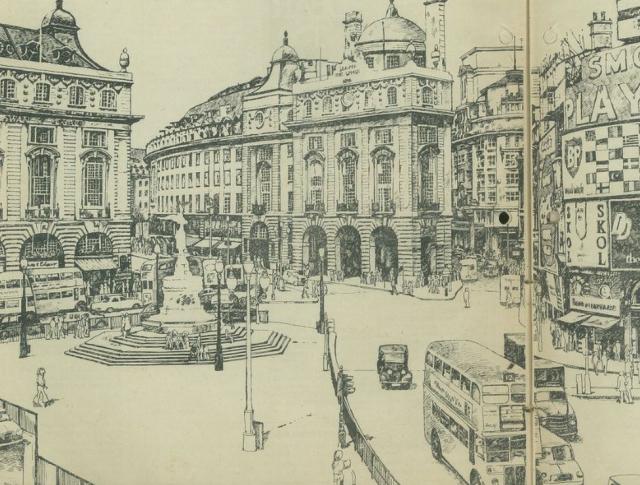

Then there was Bollywood. “We are not very rich people,” Amitabh Bachchan told JS, which spent four days with the actor for a cover story. Mr Gopinath, the keenly observant correspondent, wrote he didn’t quite believe the star because he saw the “Toyotas and Merces in [his] leafy driveway, the smell of Aramis after shave in the crowded make-up room, the numerous packs of Dunhill cigarettes, the lunchtime talk of days spent shopping in Piccadilly [Circus]”.

JS was also ahead of its times in many ways. At a time when few Indians could afford to travel abroad, the magazine went to New York and London, publishing long travelogues with illustrations and pictures – “If London can surprise with serendipity, New York can baffle with elusiveness,” said a florid piece.

Years before leading newspapers started inviting celebrities to guest-edit for a day, JS gave actor Jalal Agha the reins as editor “for half an hour”. During this brief stint, Agha playfully “stomped around the office like a crazed, plump Bugs Bunny, causing havoc, despair, and semi-permanent damage” – a whimsical episode vividly captured in a series of gleeful pictures.

JS reporters ventured into remote locations to cover stories on handcrafted goods like carpets, denims, and silk saris when mainstream media lacked such detailed coverage. They delved into the Dalit Panthers’ fight against caste barriers in Bombay, reported on the 1967 Maoist rebellion in rain-soaked Naxalbari, and even journeyed to Bhutan for a new king’s coronation.

In their pursuit to understand the lesser-explored aspects of India, JS spent time in a dusty town, Mirzapur in Uttar Pradesh, vividly describing its bustling yet socially rigid atmosphere in 1975.

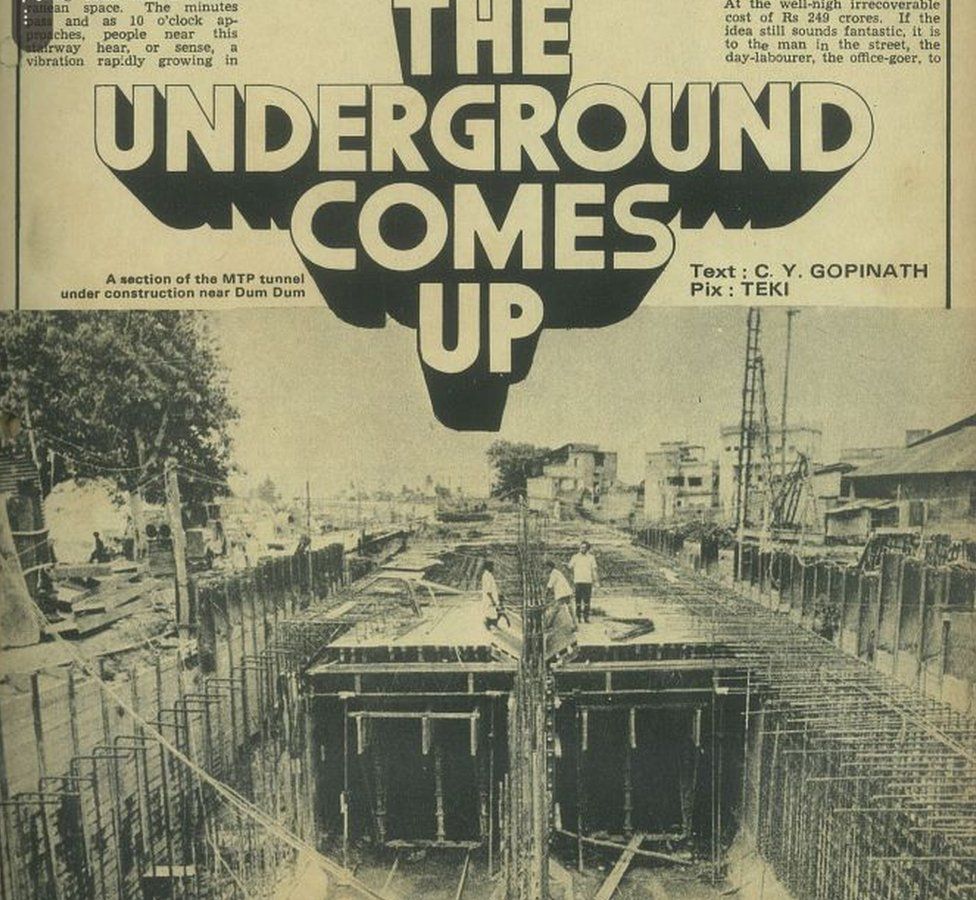

One of their significant reports in 1976 was an in-depth coverage of Kolkata’s first underground metro construction, which spanned over 12 years. The excavation process uncovered intriguing relics such as old handcuffs, bullet shells believed to be remnants of WWII, and even some not-so-old gold coins. The neighborhoods affected by the construction seemed temporarily lifeless, as if drained of vitality.

Before the rise of confrontational TV debates, JS hosted thoughtful face-offs between differing viewpoints. They introduced ‘We took Ten,’ where randomly selected young individuals shared their perspectives on various topics, predating the concept of opinion polls. Additionally, notable Bollywood personalities like Rekha, Zeenat Aman, and Simi contributed beauty and advice columns for JS long before celebrities became regular contributors in media.

The 60-page weekly publication was filled with surprises, hosting events like ‘JS Happenings’ where their mascot, a 1932 Ford vintage car painted in vibrant psychedelic colors, took the spotlight. Another intriguing section was the ‘JS Exchange,’ a barter column where one post stood out: “Sixteen-year-old female seeking friends who share interests in Ravi Shankar, Rolling Stones, and Rajesh Khanna for picnics, parties, etc. Parent-approved boys welcomed.”

Despite criticism branding JS as “frothy and un-Indian,” accusing it of promoting Westernization through denim and pop music, Mr. Suraiya passionately defended the magazine. He saw JS as a voice speaking to an urban, educated cultural sensibility that, while influenced by the West, was shaping a unique Indian cosmopolitanism.

Unexpectedly, in 1977, the publication met a brutal and sudden end, leaving its 40,000 paid subscribers and numerous readers bewildered. The Statesman abruptly halted the presses mid-print of an issue featuring a cover story on tea gardens, closing down the magazine without clear reasons. Ms. Karkaria lamented the closure, citing that JS had defined Indian teenage identity but left that demographic adrift when it was shut down abruptly, leaving behind a new style of journalism never seen before.

Mr. Suraiya, the magazine’s prolific writer, penned an epitaph for the premature demise of a youthful dream. He likened JS to Camelot—a realm of promise, fleeting yet ever-enduring. He spoke of the eternal nature of youth, its wonder, its frustration, and its moments of pure joy that echo as sharply as pain. To him, JS embodied this essence—forever alive in memory and spirit.

Acknowledgments to singer-songwriter Jaimin Rajani and Chandni Doulatramani for their contributions.

Source: BBC News

Disclaimer:

This content is AI-generated using IFTTT AI Content Creator. While we strive for accuracy, it’s a tool for rapid updates. We’re committed to filtering information, not reproducing or endorsing misinformation. – Jomotoday for more information visit privacy policy

1 Comment